Are quitters winning?

Digging deeper into the “Great Resignation”

The tightening labor market in the U.S. has been one of the major economic stories of the second half of 2021, as recently released employment figures show. The unemployment rate fell to 4.2 percent in November, the lowest since March of 2020. Meanwhile, labor force participation increased to 61.8 percent, signaling that—barring a major Omicron-related speedbump—the long-sought post-pandemic equilibrium in the labor market may finally be approaching.

But as Avison Young’s U.S. Employment Tracker shows, this recovery has not been uniform. The leisure and hospitality sector, for example, is still down over 1.3 million jobs, almost 8 percent below its former level. Even in some office-using sectors, such as state and local government, employment remains lower than before.

Against this turbulent background, the phenomenon dubbed the “Great Resignation” has emerged in the past few months. For most of 2021, there has a been clear upward trend in people quitting their jobs. After a record 4.4 million people voluntarily left their places of employment in September, another 4.2 million quit in October. This is about 25 percent more than in a typical month during 2019. And just as the recovery itself has important sector-specific aspects, so too does the story of the Great Resignation.

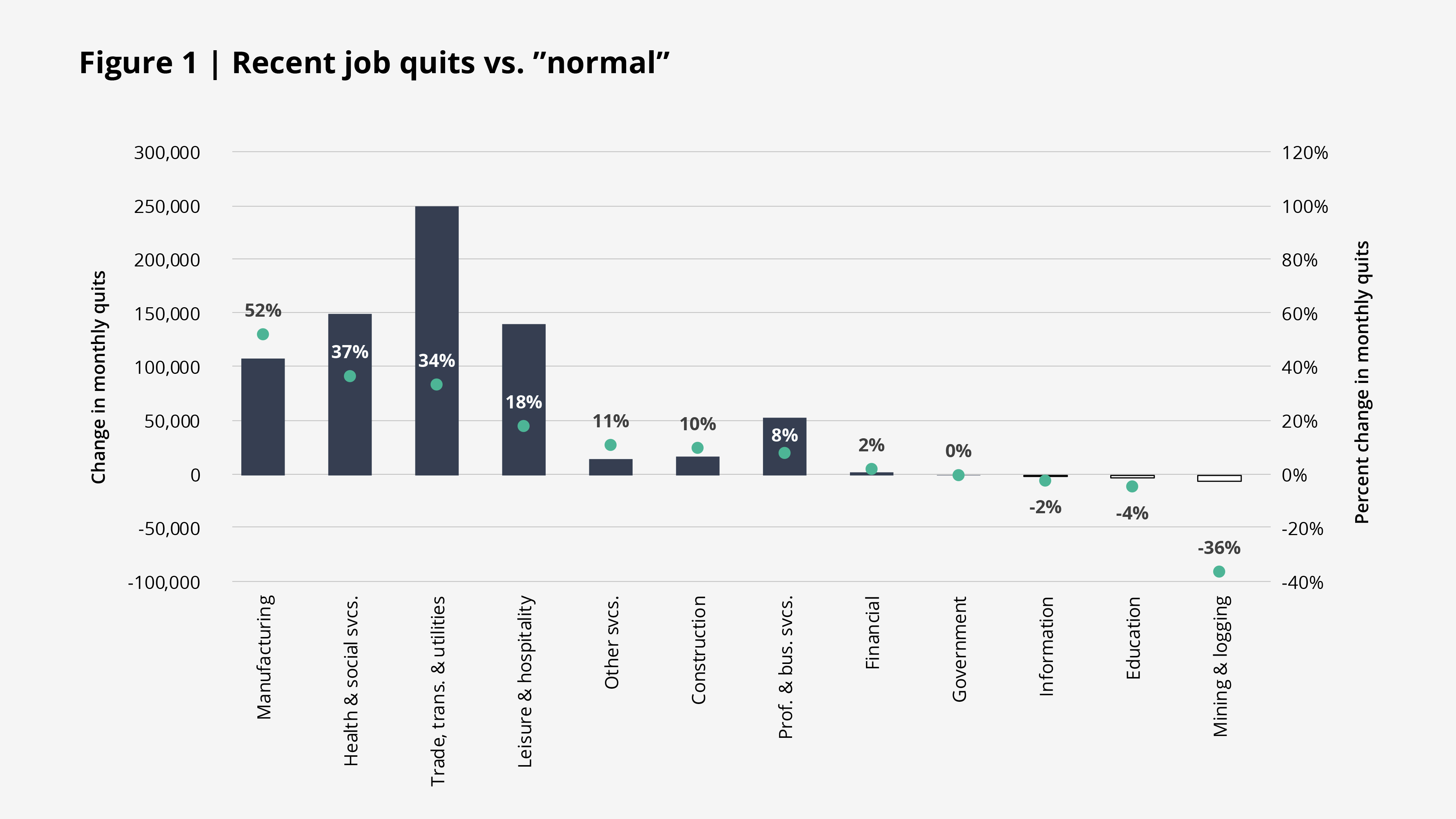

Employment figures from the Bureau of Labor Statistics show that the increase in the quitting trend is much more pronounced in some industries than in others. In industries that historically have relatively high turnover, quit rates have moved even higher.[1] As Figure 1 shows, there were more than a quarter of a million more quits per month in Q3 within the trade, transportation and utilities sector than in “normal” times—an increase of 34 percent. Similarly, the healthcare and social services sector saw over 150,000 excess resignations, 37 percent above normal.

The additional 141,000 quits in the high-churn leisure and hospitality sector represent an 18 percent increase. And in manufacturing, quits rose 52 percent.

Note: Monthly average quits in Q3 2021 vs. 2019 for each sector, all data seasonally adjusted

Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics Job Openings & Labor Turnover Survey

In other sectors—particularly office-using industries—the story is more nuanced. In the professional & business services category (which includes technology and software), monthly resignations are up by over 50,000, or about 8 percent. But the quit rate in government, finance and information services is essentially unchanged. Taken together, this suggests that the Great Resignation is large enough to be meaningful among knowledge workers but is dwarfed in both velocity and magnitude by what is occurring among blue-collar and service-sector workers.

Why is this happening?

Anecdotes about the reasons for increasing resignations abound in media reports. One such plausible story is that office workers are resisting calls to return to corporate offices , choosing instead to resign in favor of jobs that offer increased flexibility to work remotely (in addition to higher pay) There are surely many instances of this happening, including those leaving to work independently. Yet, the finance sector has stood out for its call on employees to return to offices and, as noted above, has not seen an increase in quits. Furthermore, most major office occupiers have delayed their return-to-office (RTO) plans until 2022, and a majority plan to offer some form of the hybrid workplace that offers more flexibility. It seems unlikely that RTO would have already been a primary driver of quitting for most knowledge workers.

In other sectors, however, the data provides circumstantial support for common explanations of why the Great Resignation might be happening. In leisure and hospitality, for example, the story goes that the spigot of pent-up consumer demand has overwhelmed the trickle of rehiring, leading to short-staffing, long hours, and angry customers. (See our Vitality Index to monitor the recovery of foot traffic in various locations and industries.) In this environment, more quitting is to be expected. Similarly, the ecommerce wave crested suddenly, stressing the transportation and logistics industry with a surge in customer demand for products that jammed up warehouses, roads and ports. Workers in this sector quickly found out just how essential they are in the form of increased productivity quotas and overtime. It is not surprising that many of them would burn out.

What about COVID?

Another theory is that COVID-related mandates for vaccination and/or on-the-job masking and distancing could be causing a wave of resignations This is not easy to investigate, but one proxy might be analyzing quits in relation to state-by-state vaccination rates. One would expect states with lower adult vaccination rates to have a higher concentration of workers who might object to workplace regulations in general and vaccine mandates in particular. If those same states were also seeing higher quit rates, it could be a sign that workers are quitting over COVID-related restrictions.

In fact, there is a relationship between the vaccination rate and resignations in a given state. Figure 2 shows that states with lower vaccination rates tend to have higher quit rates. The relationship is strong enough (R2=22%) to warrant attention.

Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics Job Openings & Labor Turnover Survey, CDC

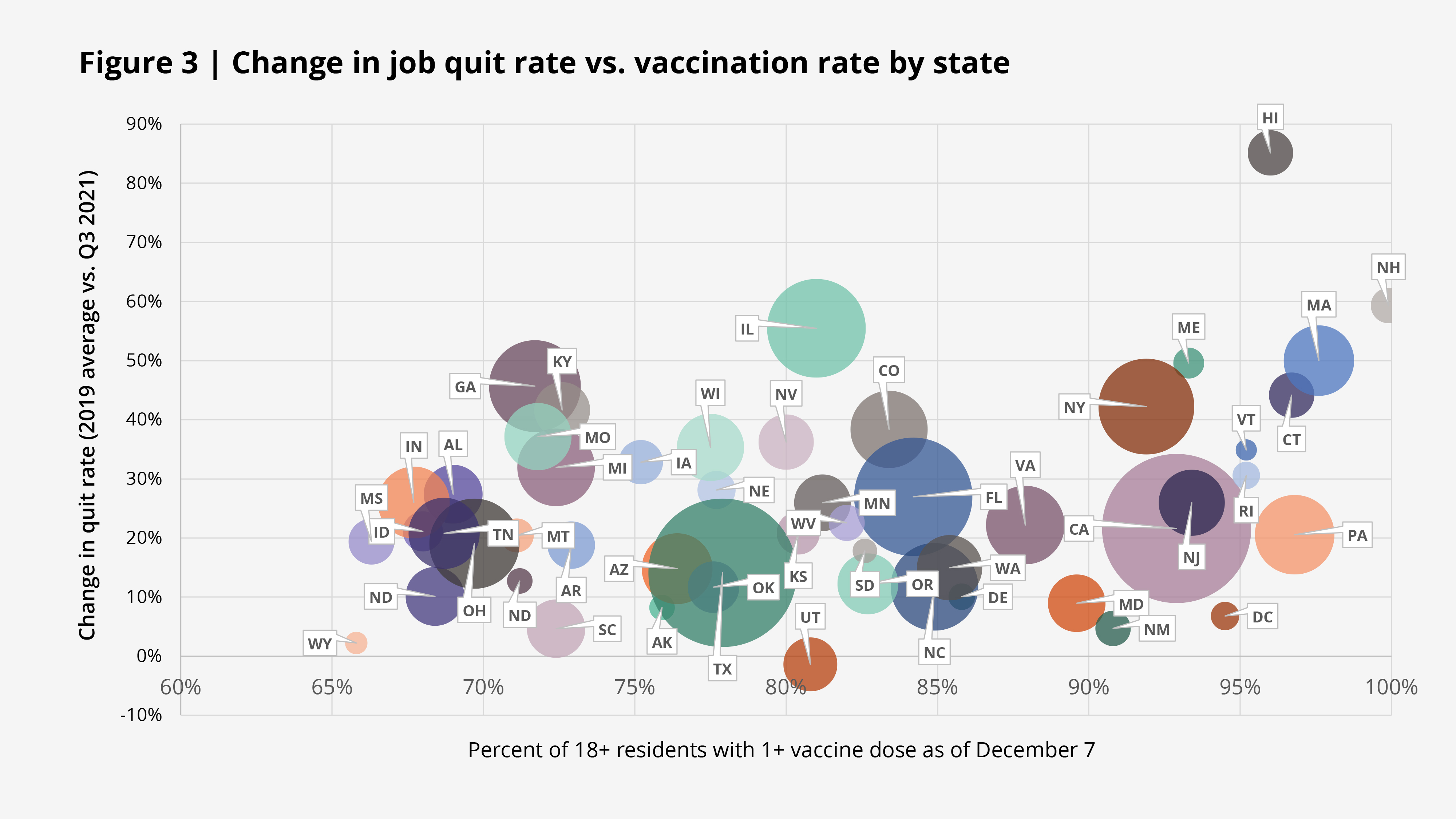

Note: Bubble size represents the current relative number of monthly quits in each state

On the other hand, it could be that quitting is more common in these states in general, for reasons unrelated to COVID restrictions. Analyzing the change in quitting since 2019 reveals a different pattern, as Figure 3 depicts.

Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics Job Openings & Labor Turnover Survey, CDC

Note: Bubble size represents the current relative number of monthly quits in each state

Here, a higher vaccination rate in a state is associated (R2=12%) with a greater increase in the rate of quitting. This, however, could also be taken as evidence that COVID restrictions are behind a portion of resignations. Workers in manufacturing, transportation, healthcare and leisure/hospitality tend to come from demographics with lower rates of vaccination. If they are working in high-vaccination states that nevertheless impose more restrictions, it is possible that they would be even more likely to quit than their counterparts in low-restriction states. While this is not conclusive evidence that COVID-related workplace regulations are driving large numbers of resignations, it does suggest they could be a factor in some of them.

What can we expect next?

What does all this quitting mean for the near future? What should we expect the end game to be? For one thing, it is a sign that workers now have the upper hand, however temporarily. This should result in lower unemployment, recovering labor force participation and higher wages. And we are already seeing all three.

As noted above, unemployment reached its lowest point since the beginning of the pandemic last month. Wages are increasing as well, particularly on the lower end of the scale. In the leisure and hospitality sector, for example, they increased by 11.2 percent (annualized) in October, far above even the relatively high levels of inflation in the same period.

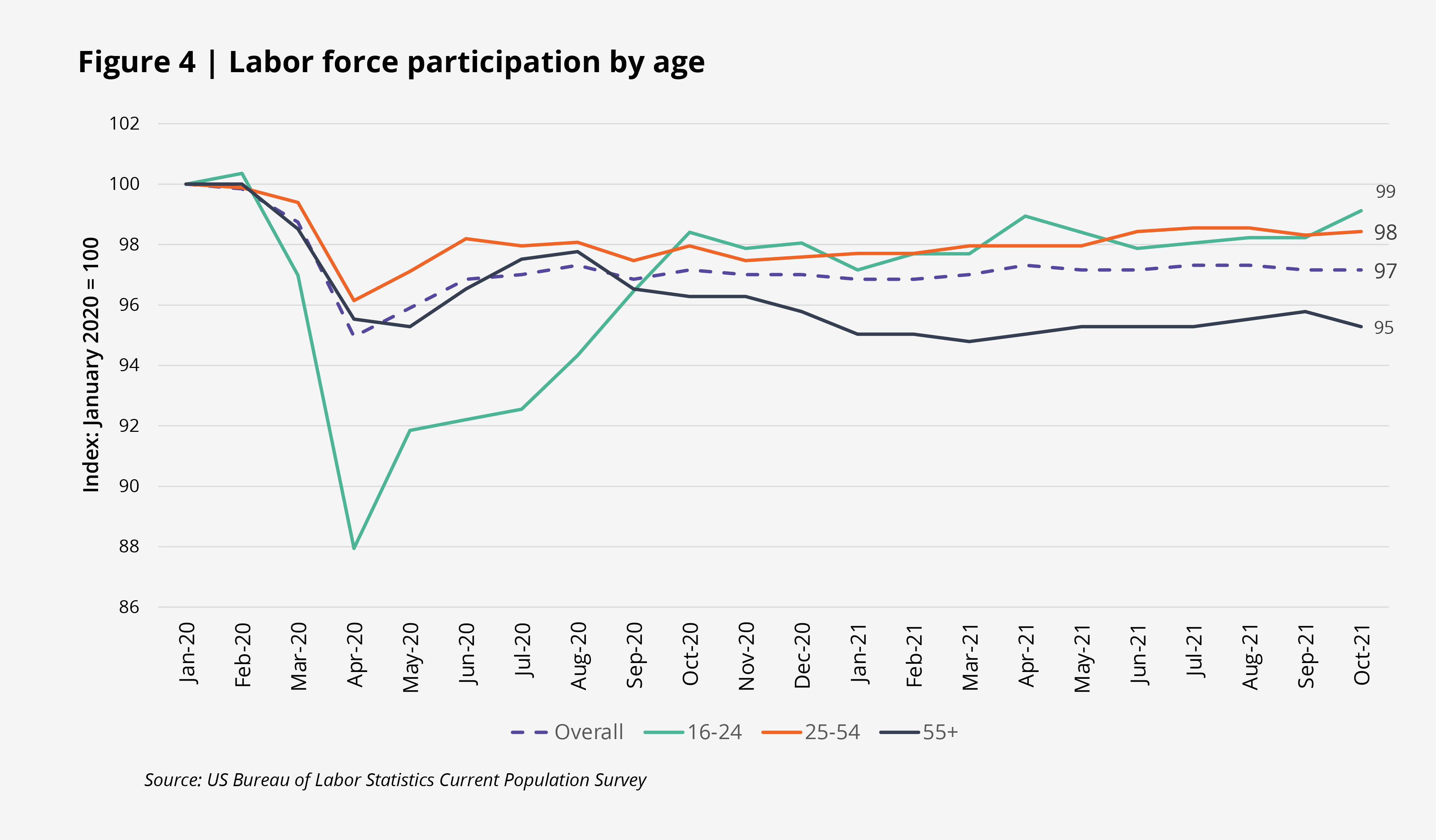

Even more interesting is the labor force participation rate. It remained steady at 61.6 percent in October despite higher wages. But the reality is that most workers are already back, and those who are not may not be influenced by higher wages. Figure 4 shows labor force participation by age. Younger workers (those 16-24, all of whom are part of Gen Z) dropped out of the labor force in large numbers in the spring of 2020. But by the end of the year, they were mostly back, as were their Millennial and Gen X counterparts. By October 2021, participation in these age groups had recovered nearly to the level of January 2020.[1] It is evident, then, that most job quitters are choosing to seek new employment rather than drop out of the labor force (or, if not, that they are being replaced by their peers.) With rising wages, along with the relatively high number of job openings, we should expect this recovery to be complete in the coming months—barring another COVID-related shock, that is.

Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics Current Population Survey

It is the trailing end of the Baby Boomer generation that has been slow to return to the labor force, and some may indeed never do so. Rising home values, increased household savings and a general sense of having run their course could all be contributing to an early and permanent—if unplanned—exit for workers aged 55 and older. This would have implications for the mentorship and development of younger workers but should open up plenty of opportunity for advancement and higher pay.

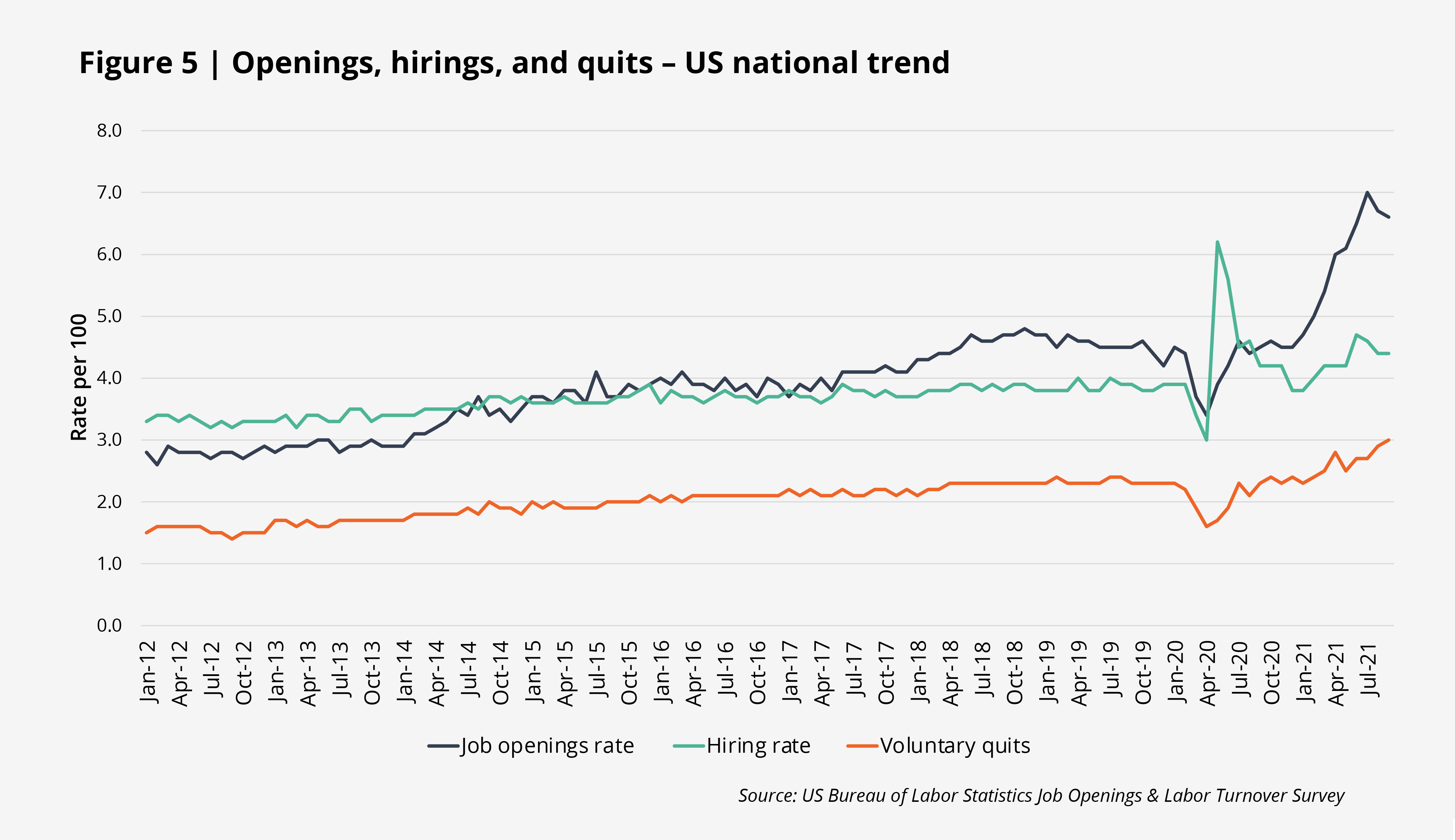

Also of note is the fact that what we now call the Great Resignation appears to be the continuation of a much longer-term increase in the job quit rate. Figure 5 shows the steady rise from about 1.5 per 100 in 2012 to over 2 per 100 that by the end of 2019. That it has now accelerated to nearly 3 per 100 may not be an aberration. Instead, the pandemic-related shocks may have served to empower workers to take action to improve their wages and workplace experience. The fact that the job openings and hiring rates have also moved higher should only strengthen their hand.[2]

Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics Job Openings & Labor Turnover Survey

Conclusion

The second half of 2021 has seen an unprecedented number of voluntary resignations, which is remarkable given the historic layoffs that happened just 20 months ago. The quitters are largely in blue-collar and service-sector professions, and most of them are remaining in the labor force, where they will undoubtedly be looking for higher wages and better working conditions—as indeed many have been doing for years. Abundant openings and rising wages mean that if there was ever a time for quitters to win, it is now.

[1] Perhaps surprisingly, there now is a negligible difference in labor force participation by gender as compared to pre-pandemic levels.

[2] Immigration is not addressed in this piece, as official figures for 2020 and 2021 are not yet available; however, it is clear that because of COVID-19, immigration has been lower than it was in the years prior to 2020. This has reduced the overall size of the labor force, further increasing the leverage of existing workers and current residents who could become job seekers.

Phil Mobley is our Director of U.S. Occupier Insight, based in Boston.