What is the future for London’s Industrial Economy?

In this blog post, we reflect on Avison Young’s involvement in the recently published London Industrial Land Supply and Economic Study 2020 and investigate some of the trends that will shape the future of the industrial sector in London.

The Industrial sector has experienced a resounding rise to prominence in recent years. In the commercial property sphere, it is a sector that had so often been overlooked in favour of the more glamorous worlds of offices, or retail. But, changing consumer habits, the need for supply chain resilience, and growing requirements for highly sustainable buildings which offer a quality working environment have led to strong demand at a time of diminishing supply.

Amidst all of this, we have seen a broadening of industrial activity, which is driving occupational and investor demand for a whole host of spaces. Now, perhaps more than ever before, industrial land and property is an integral part of the ecosystem relied upon to meet the day-to-day needs of London, its people and businesses. This has been discussed in more detail within a Centre for London report supported by Avison Young.

Our involvement in the London Industrial Land Supply and Economic Study, a data driven analysis of London’s industrial economy, has indicated some stark, market-driven trends that will influence the industrial landscape in the years to come. For policy makers, occupiers, investors/developers, and others, awareness of these challenges, and a strategic, targeted response will be critical to ensure the continued vitality of the sector.

The challenges

Squeezed Supply

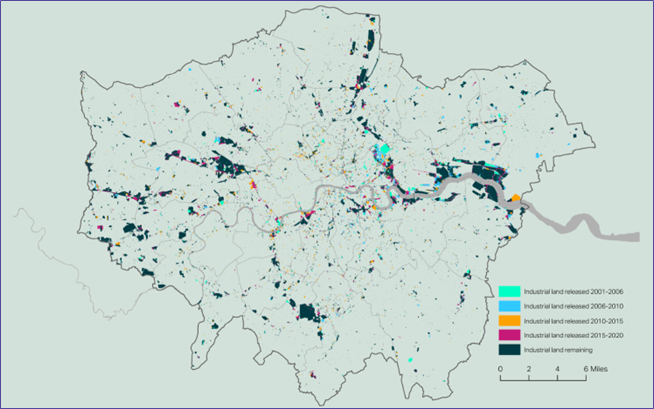

Industrial land supply in London has shrunk significantly over the last 20 years. Loss of land has occurred at the most significant rate in the last 5 years. The planning pipeline signifies that this trend is set to persist at an unprecedented rate in the future.

The study indicates that land in industrial use in London has seen continued decline over the last 20 years, with heavy pressure from competing land uses, and particularly residential use. Between 2001 and 2020, 1,500 ha (18%) of industrial land has been lost.

This trend is particularly pronounced in the last 5 years. The 2017 London Industrial Demand Study recommended a benchmark release of 232 ha between 2016 and 2041. In reality, between 2015 and 2020, there has already been a loss of 352 ha, demonstrating erosion of land beyond the recommended release in all sub-regions(1) . This has been most stark in East London but remains a significant challenge across the city.

This trend is particularly pronounced in the last 5 years. The 2017 London Industrial Demand Study recommended a benchmark release of 232 ha between 2016 and 2041. In reality, between 2015 and 2020, there has already been a loss of 352 ha, demonstrating erosion of land beyond the recommended release in all sub-regions(1) . This has been most stark in East London but remains a significant challenge across the city.

Figure 1: Industrial Land Release 2001 - 2020

Source: AECOM, London Industrial Land Supply and Economic Study, 2020

Looking forward, there is an estimated 736 ha of land in industrial and related uses in the planning pipeline that could potentially change to non-industrial uses(2). This will present even greater pressure on supply of land. About 30% of this is proposed local plan release from SIL or LSIS designations, identified in the London Plan as London’s largest concentrations of industrial, logistics and related capacity for uses that support the functioning of London’s economy. In the context of recent Government announcements, supporting residential development within inner-city locations, this pressure is likely to increase further.

This loss of industrial land will have direct implications for floorspace, with a chronic (and worsening) undersupply of industrial stock. Floorspace capacity is already very tight, with vacancy currently sitting at 3.2% across London. With unprecedented loss of industrial land anticipated, we envisage some acute supply challenges in the coming years.

This challenge is exacerbated when we consider the quality of the existing inventory of industrial stock across London. At least 60% of buildings were completed or last renovated prior to 2000. Conversely, just 4% of stock was completed/last renovated post-2010. In the context of MEES regulations, which require all properties being let to achieve an EPC rating of E (with this due to rise to B by 2030) obsolescence remains a critical risk.

Combined, an under-supply of industrial stock, and a high risk of obsolescence present great supply-side challenges.

This loss of industrial land will have direct implications for floorspace, with a chronic (and worsening) undersupply of industrial stock. Floorspace capacity is already very tight, with vacancy currently sitting at 3.2% across London. With unprecedented loss of industrial land anticipated, we envisage some acute supply challenges in the coming years.

This challenge is exacerbated when we consider the quality of the existing inventory of industrial stock across London. At least 60% of buildings were completed or last renovated prior to 2000. Conversely, just 4% of stock was completed/last renovated post-2010. In the context of MEES regulations, which require all properties being let to achieve an EPC rating of E (with this due to rise to B by 2030) obsolescence remains a critical risk.

Combined, an under-supply of industrial stock, and a high risk of obsolescence present great supply-side challenges.

Deepening Demand

Against this supply context, industrial demand is at unprecedented levels across a whole host of uses and unit sizes. This demand/supply imbalance is driving strong rental value and capital value growth.

There has been significant growth in demand for logistics stock fuelled by changing consumer habits and the growth of e-commerce, a focus on supply chain resilience and buildings which perform well in respect of ESG criteria. This has focused on key locations with good access to the strategic road network including the likes of Ealing, Barking and Dagenham and Enfield. In addition, demand is growing for final mile distribution space (which typically focuses on smaller floorplates near residential areas).

The strength in demand for stock of this nature, relative to the existing undersupply has been a significant factor driving increased industrial rents, capital values and land values across London. As the strength in demand is set to continue, a growing development pipeline for logistics stock and continued upward pressure on rents and values are likely.

However, the scope of demand extends beyond logistics alone and there are a broad range of industrial uses competing for space. There has been a surge in demand for data centres, driven by increased digitalisation of commercial operations, generating demand for big box stock. Whilst we understand demand is now cooling off, the spike in requirements for Film and TV production / post-production for large floorplate space in Outer London is also demonstrative of the broadening of industrial demand beyond traditional B-class uses in recent years.

And amidst all of this, general demand for smaller, more local 'producers' wanting to be in London endures. The depth of demand with which these critical uses must compete is driving significant value inflation and presents real challenges to London’s industrial ecosystem.

The study indicated average industrial rents at £19psf – which reflects a 36% uplift on the 10-year average of £14psf. Capital values reflected an even steeper trend, seeing a 64% uplift on the 10-year average to reach £325psf. Notably, these reflect average values, and there are instances of far higher values being seen in inner areas, and for better quality stock. These value shifts are indicative of a market with extremely tight, and worsening supply, against a growing basis of demand across a broader range of unit typologies.

It should be noted that the data reported on reflects trends at a point in time, with much of the data informing the study collected through 2021. The industrial sector is evolving rapidly, and there have since been market changes. Across the latter half of 2022, yields moved out by 150-200 basis points, causing development land values in many cases to fall by 50-60%. Pricing is stabilising but capital values have shrunk. With rampant cost inflation now tailing off, our agents indicate that yields might come in slightly. However, rents must remain high or even increase to offset costs and low land values to ensure viability. This will therefore continue to drive affordability challenges.

The strength in demand for stock of this nature, relative to the existing undersupply has been a significant factor driving increased industrial rents, capital values and land values across London. As the strength in demand is set to continue, a growing development pipeline for logistics stock and continued upward pressure on rents and values are likely.

However, the scope of demand extends beyond logistics alone and there are a broad range of industrial uses competing for space. There has been a surge in demand for data centres, driven by increased digitalisation of commercial operations, generating demand for big box stock. Whilst we understand demand is now cooling off, the spike in requirements for Film and TV production / post-production for large floorplate space in Outer London is also demonstrative of the broadening of industrial demand beyond traditional B-class uses in recent years.

And amidst all of this, general demand for smaller, more local 'producers' wanting to be in London endures. The depth of demand with which these critical uses must compete is driving significant value inflation and presents real challenges to London’s industrial ecosystem.

The study indicated average industrial rents at £19psf – which reflects a 36% uplift on the 10-year average of £14psf. Capital values reflected an even steeper trend, seeing a 64% uplift on the 10-year average to reach £325psf. Notably, these reflect average values, and there are instances of far higher values being seen in inner areas, and for better quality stock. These value shifts are indicative of a market with extremely tight, and worsening supply, against a growing basis of demand across a broader range of unit typologies.

It should be noted that the data reported on reflects trends at a point in time, with much of the data informing the study collected through 2021. The industrial sector is evolving rapidly, and there have since been market changes. Across the latter half of 2022, yields moved out by 150-200 basis points, causing development land values in many cases to fall by 50-60%. Pricing is stabilising but capital values have shrunk. With rampant cost inflation now tailing off, our agents indicate that yields might come in slightly. However, rents must remain high or even increase to offset costs and low land values to ensure viability. This will therefore continue to drive affordability challenges.

Our Reflections

So, what does this all mean for the future of the industrial sector? These challenges are complex, and heavily embedded within supply and demand dynamics. There will be no quick fixes, but co-ordinated action from key stakeholders will be critical to support the continued vitality of the sector. We set out below 5 key themes that will be critical as the sector weathers these challenges:

1) MEES and environmental credentials

Given the already significant demand and supply imbalance, safeguarding (and refurbishing) existing industrial stock will be critical. The risk of obsolescence given MEES regulations will need to be managed through active refurbishing to prevent erosion of stock. In an inflationary environment, there remain important questions around access to funding streams to support this activity. Owners of lower value stock may have less readily available access to capital, yet remain the most at risk of obsolescence.

2) Fit-For-Purpose

In addition to environmental objectives, it will also be important to ensure existing stock is fit-for-purpose. With broadening demand for a range of non-typical industrial uses, it will be crucial that policy makers shape a supportive framework that provides investors/developers with maximum flexibility to meet the evolving needs of occupiers. This will need to be balanced against protection of important uses, and firm enforcement of existing designations.

3) Innovative Delivery

A key consideration will be finding optimal ways to deliver additional capacity. We anticipate that trends such as the rise of final mile distribution will generate a need for SIL and LSIS designations in more central locations than has been the case historically. A pro-active policy approach to these issues will be required to deliver the ‘right’ space in the ‘right’ locations.

Given the scarcity of land in more central locations, industrial intensification and co-location will be a key component of the delivery solution. An adequate policy stance, active engagement with occupiers and the market to ensure suitability of space that minimises compromise on quality, and careful thought to viability in the context of higher land values and development costs in central locations across multi-storey unit configuration will all be important to achieve high-quality new supply. Given residential supply-side issues, and recent Government announcements on inner-city development, co-location will continue to be a key theme.

Opportunities for conversion of alternative uses to industrial use will exist. This will need to be driven by pro-active policy and innovative delivery approaches to ensure delivery in the right locations. For example, given proximity to suburban populations, site-sizes and configuration, out-of-town retail parks could present good opportunity for conversion to urban logistics. Car parks may present a good opportunity in more central areas where land supply is tighter.

4) Electric Vehicles and Energy

With the growth in electric vehicles, thought will need to be given to how industrial stock evolves.

Electric vehicles will require on-site charging. This of course has implications for space, and for energy consumption. Both challenges will need to be considered and addressed to support delivery.

5) Affordability

The demand/supply fundamentals mean that one thing will be certain – affordability challenges will endure. Rental growth is pricing traditional industrial occupiers out of the market. The average rents cited within the study go some way to demonstrating the issue, but critically, they underplay the full extent of affordability challenges being experienced in higher value inner areas. Pricing adjustments following widespread refurbishment of dated stock will likely be an unintended consequence of the extension to MEES regulations.

Amidst refurbishment and delivery of new supply, careful thought will need to be given to policy levers and other mechanisms that support the continued functioning of the broad range of businesses that support London’s diverse industrial economy. Patrick’s Ransom’s recent series on affordable workspace provides excellent insight on this.

1) MEES and environmental credentials

Given the already significant demand and supply imbalance, safeguarding (and refurbishing) existing industrial stock will be critical. The risk of obsolescence given MEES regulations will need to be managed through active refurbishing to prevent erosion of stock. In an inflationary environment, there remain important questions around access to funding streams to support this activity. Owners of lower value stock may have less readily available access to capital, yet remain the most at risk of obsolescence.

2) Fit-For-Purpose

In addition to environmental objectives, it will also be important to ensure existing stock is fit-for-purpose. With broadening demand for a range of non-typical industrial uses, it will be crucial that policy makers shape a supportive framework that provides investors/developers with maximum flexibility to meet the evolving needs of occupiers. This will need to be balanced against protection of important uses, and firm enforcement of existing designations.

3) Innovative Delivery

A key consideration will be finding optimal ways to deliver additional capacity. We anticipate that trends such as the rise of final mile distribution will generate a need for SIL and LSIS designations in more central locations than has been the case historically. A pro-active policy approach to these issues will be required to deliver the ‘right’ space in the ‘right’ locations.

Given the scarcity of land in more central locations, industrial intensification and co-location will be a key component of the delivery solution. An adequate policy stance, active engagement with occupiers and the market to ensure suitability of space that minimises compromise on quality, and careful thought to viability in the context of higher land values and development costs in central locations across multi-storey unit configuration will all be important to achieve high-quality new supply. Given residential supply-side issues, and recent Government announcements on inner-city development, co-location will continue to be a key theme.

Opportunities for conversion of alternative uses to industrial use will exist. This will need to be driven by pro-active policy and innovative delivery approaches to ensure delivery in the right locations. For example, given proximity to suburban populations, site-sizes and configuration, out-of-town retail parks could present good opportunity for conversion to urban logistics. Car parks may present a good opportunity in more central areas where land supply is tighter.

4) Electric Vehicles and Energy

With the growth in electric vehicles, thought will need to be given to how industrial stock evolves.

Electric vehicles will require on-site charging. This of course has implications for space, and for energy consumption. Both challenges will need to be considered and addressed to support delivery.

5) Affordability

The demand/supply fundamentals mean that one thing will be certain – affordability challenges will endure. Rental growth is pricing traditional industrial occupiers out of the market. The average rents cited within the study go some way to demonstrating the issue, but critically, they underplay the full extent of affordability challenges being experienced in higher value inner areas. Pricing adjustments following widespread refurbishment of dated stock will likely be an unintended consequence of the extension to MEES regulations.

Amidst refurbishment and delivery of new supply, careful thought will need to be given to policy levers and other mechanisms that support the continued functioning of the broad range of businesses that support London’s diverse industrial economy. Patrick’s Ransom’s recent series on affordable workspace provides excellent insight on this.

(1)Within the LILSES, sub-regions split London Boroughs into core groups of Central, North, East, South and West.

(2)Metric considers unimplemented planning permissions, previously designated sites, and proposed local plan release.

(2)Metric considers unimplemented planning permissions, previously designated sites, and proposed local plan release.